I’ve been so slow to add this last part of my grandfather’s story, because it has been the hardest to make sense of.

Did Michael Bastian John know he was dying, as the months slipped by in 1934 and he was heading towards his 52nd birthday at a time when not many people in Malaya made it past their mid-50s?

He had outlived relatives and acquaintances who had travelled like him from Travancore at the turn of the century to make a new life in Southeast Asia. Over his three decades in Malaya, he would have attended funerals of men and women he knew, family too, who died in their 30s, or even younger.

And then, what was that great calamity that struck, costing him everything he had, that would leave his wife Isabella and their 10 children in dire straits when he passed on?

I turn the fragile pages of his diary in my cousins’ home in Taiping, searching through the notes he scribbled in 1933 and 1934 for some clue, anything at all.

It appears that it took only a matter of months for my grandfather to turn from the dapper fellow making silk suits for himself, who went shopping for a necktie and new shoes, to a man who seemed to be struggling with sadness, regret and loss. Perhaps shame too.

Did he have some kind of premonition? Was he weighed down spiritually, emotionally, physically in the months before he died on September 20 1934, nine days before he would have turned 52? I do not even know what he died of.

But in some pages of that diary, there are hints he might have been in turmoil, overwhelmed by something gone awry.

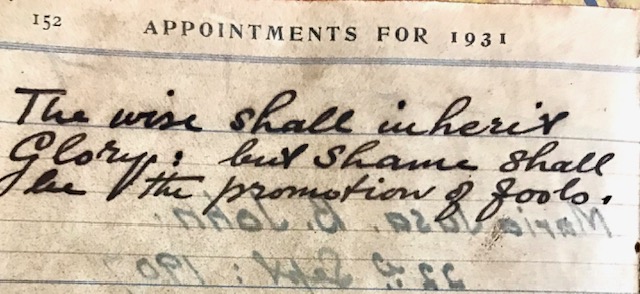

I come across the only line from the Bible that my grandfather chose to write down:

“The wise shall inherit Glory, but shame shall be the promotion of fools.” Proverbs 3:35

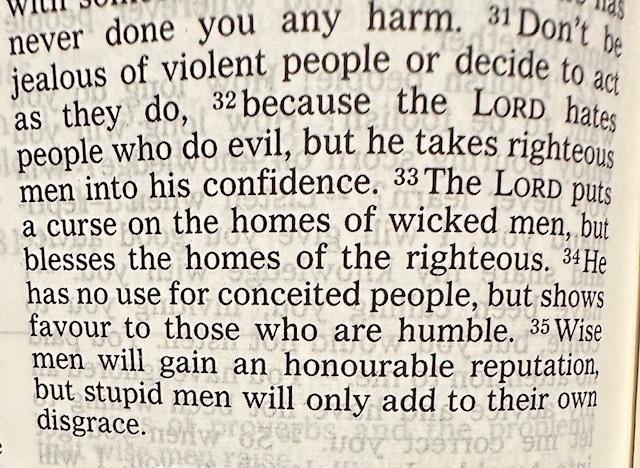

My Good News Bible states it more plainly: “Wise men will gain an honourable reputation, but stupid men will only add to their own disgrace.”

Did Michael Bastian John approach the final days of his life filled with shame for having thrown everything away through some wrongdoing or recklessness, and was he mortified at the prospect of being remembered only as a fool?

Why this line, out of everything else in the Bible? Nowhere else does he come this close to saying a prayer and now it strikes me like a cry of desperation.

If that line from Proverbs made me pause and wonder, two other pages in that diary break my heart.

On Page 150, my grandfather wrote:

“The names shown on Page 151 are members of my family, died and buried in K. Lumpur. Unfortunately I had no chance even to put a cross on their graves for their memory.

“Through the help of Almighty God and through the intersection (sic) of Souls in purgatory, I promise on the first opportunity I get some money in my hand I will lay a cross on the grave and perform a R.H. Mass for the souls of [illegible].”

On Page 151 he wrote a list of names:

Maria Jusa B. John, 22nd Sept 1907

Victoria Rozario, About the year 1910

Constantine D. Lopez, 26 July 1914

Carmen D. Lopez, 26 Jan 1912

Louisa D. Colandasamy, 30th Sept 1922

Bertha M. John, 25th April 1921

I know the last two names.

Louisa D. Colandasamy was his sister, who had five sons, including my father, John. She was 36 when she died.

Bertha M. John was Michael and Isabella’s fourth child, who died in infancy.

Was Maria Jusa B. John his sister too? If the B stood for Bastian, they were siblings, and that meant he had three sisters in Kuala Lumpur – Louisa, Maria and unmarried Agnes, who lived with him and Isabella and helped raise their large brood.

Could Victoria Rozario have been a sister-in-law? Isabella had three brothers and a sister in Malaya – Joseph, William and Victor Rozario and Francina Rozario Pereira. Was there another sister?

Constantine D. Lopez was the father of Romuald Constantine Lopez, who was godfather to two of John and Isabella’s children, Bertha and my mother, Agnes. Carmen D. Lopez would have been Constantine’s sister, going by that middle initial D. My grandparents were related to the Lopez family.

On these pages, my grandfather remembered family members who had died between 1907 and 1922, and recorded his sadness that he had no money to put a cross on their graves or have a Requiem High Mass celebrated for their souls.

These two pages of my grandfather’s diary filled me with a strange sorrow. For days afterwards, I could not help thinking about that list of “family members” who journeyed to Malaya and died.

His regret at having no money for a cross on their graves or a Mass for their souls is so sad. And yet, it did not make sense when only months before, he was making new suits for himself.

Was he counting the ways he had been foolish, the ways he had added to his own disgrace?

But this is as far as I can go. Michael Bastian John’s notes in the diary come to an end. His notes here and in his House Register are the only clues to the man who was my grandfather.

All the questions filling my heart must go unanswered, because there is nobody left to shed light on my grandparents Michael and Isabella.

Long after leaving my cousins’ home in Taiping, my grandfather’s words on those two pages stay with me.

To put no cross on a grave, have no Mass celebrated for a departed soul. There must be few other ways to forget those you cared for or loved, who cared for you and loved you.

I also wonder why, in this last note remembering those gone before him, my grandfather omitted mentioning Davis Colundasamy, the man who who married his sister Louisa.

More than a decade after Michael Bastian John’s death, Louisa and Davis’s second son John, my father, would pick up the old House Register and start filling in a few more pages.

To be continued.

I love reading about your family but this… oh… How very sad!

<

div>I have absolutely nothing

LikeLike

Good sharing.

LikeLike