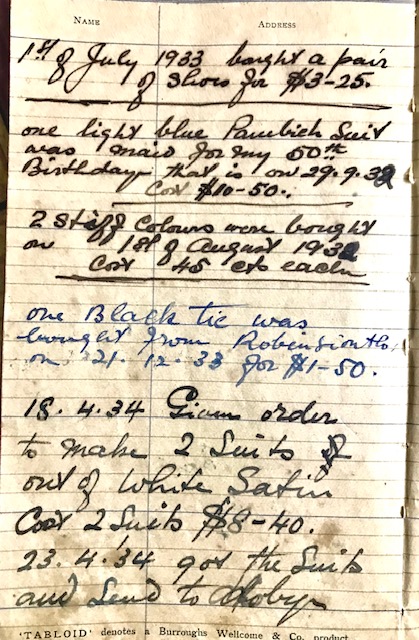

I am looking through some random notes my grandfather wrote in a diary shortly before he died and I come across this entry: “One light blue Pambich Suit was maid for my 50th birthday that is on 29.9.1932. Cost $10.50”

What on earth is a “Pambich Suit” I wonder. When I search online and cannot find a clue to anything like it, I ask Nicola, my daughter the art historian, for help.

Michael Bastian John’s great-granddaughter starts looking. She comes back after a while and tells me he might have meant a Palm Beach suit.

The Metropolitan Museum of New York website has a reference to the Goodall Worsted Co of Sanford, Maine, that bought the patent for a mohair-cotton fabric and called it “Palm Beach”.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/159547

According to the Met website: “In 1931 the company began producing suits from the fabric as well. The Palm Beach suit became a summer classic, washable and comfortable to wear; the legendary suit became the staple of the well-dressed man’s summer wardrobe.”

It has a photo too, of a comfortable cream-coloured suit that looks made of light cotton and perfect for humid Kuala Lumpur in 1932.

My grandfather, the fashion plate with a spelling problem?

Nicola says: “He may have heard on the radio that there was this new suit from America and they said it was a ‘Palm Beach’ suit, but he had never heard of the place so just wrote it down like it sounded?”

I say: “Or maybe his tailor said, ‘This pambich suit very popular in America nowadays, you want?’”

Nicola: “Who would know Palm Beach in 1930s Malaya?”

The line about the light blue suit is on a page with other entries about my grandfather’s shopping trips. Clearly he was something of “a well dressed man”.

On August 1 1932 he bought two stiff collars at 45 cents each.

On July 1 1933 he bought a pair of shoes for $3.25.

And then there’s this line: “One black tie was bought from Robinson & Co on 21.12.1933 for $1.50.”

My grandfather, a man with 10 children, a wife and an unmarried sister at home, shopped at Robinsons before Christmas?

The store founded in Singapore in 1858 attracted wealthy customers not only from the island but neighbouring countries too. According to a Singapore National Library write-up, by the turn of the 20th century, it was a household name among Europeans and the cream of Singapore society.

“Robinsons made a name for itself as a one-stop shopping paradise, with departments dedicated to haberdashery, millinery, home furnishings, bicycles, photographic apparatus, sporting equipment, and even arms and ammunitions used for game hunting,” it said. **

In 1928 a branch opened in Kuala Lumpur on Java Street, in the historic heart of town, a short walk to the new government offices, Padang and colonial club. The street was later renamed Mountbatten Road and then, Jalan Tun Perak.

I’m trying to picture this Indian man strolling into Robinsons, alongside its European and wealthy Malayan customers, picking out that black tie and paying $1.50 for it, and sauntering out of the store.

It’s just too hard to imagine.

When I was growing up in Kuala Lumpur in the 1960s, Robinsons was still a snooty store not everyone felt comfortable entering. After she remarried and briefly felt well-off, my mother would nip into Robinsons, sometimes with me in tow, to pick up a tiny bottle of Chanel No. 5, which always made her feel glamorous.

Michael Bastian John’s youngest daughter, Agnes, in the very same store.

https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-16/issue-4/jan-mar-2021/robinsons/

Five months before he died, my grandfather made himself two white satin suits. They cost $8.40 and were ready in two weeks. Where did he wear a white satin suit to? What I’d give to see a picture of him in it.

He also had clothes made for his sons.

In January, 1934, there were “two trousers and one white suit” for eldest son Justin, who was 16.

In July, he bought “6 black trousers, 3 white trousers and 9 shirts” for Cyril, nine, Alex, eight, and Teddy, seven. That cost $11.85. He added a note that he got “one dress for Charly, free of charge”. That was his youngest boy, who was three.

In June, he bought “8 saroms from Mr Guan for $12.10”. I’m guessing he meant sarongs, and that he wore them at home, like I do.

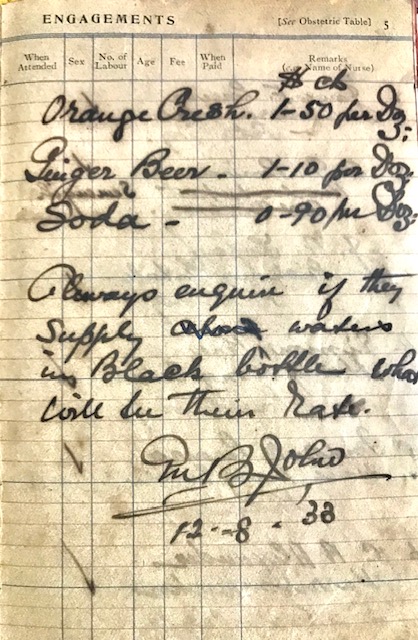

His only other notes about purchases relate to drinks. He wrote that a dozen bottles of Orange Crush cost $1.50, Ginger Beer was $1.10 and Soda, $0.90. He added a reminder to “always enquire if they supply the above waters in black bottles”.

What did it all mean? Were the stories that Michael Bastian John was well off true? If he was having clothes made for himself and his sons until months before his death, was he still flush with cash, or chalking up debts from borrowing?

He scribbled in that 1930 diary from 1932 until two months before he died on September 20, 1934.

On some pages, it is unclear if he made an entry on the day itself, or was recalling events afterwards. But I scrutinise every line for hints to know a little bit more about this man from Travancore, my mother’s father.

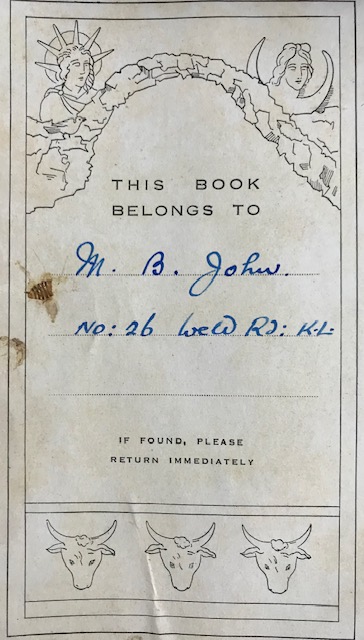

The family lived for several years in the Weld Road area, close to Bukit Nanas where St John’s Church and St John’s Institution were. The family attended services at the church, and my uncles went to the boys’ school.

Sometime in the mid 1920s, the family moved further out of town and lived at No. 13, Setapak, where my uncles Alex and Teddy and my mother Agnes were born between 1926 and 1929.

Then the family returned to 26 Weld Road, where my uncle Charlie was born in 1930 and my grandfather died four years later.

A ‘Serani Row’ mystery

Their Weld Road homes at No. 26 and earlier at No. 42 were in two-storey linked houses that stood through the 20th century.

I must have passed them countless times from the 1960s to 1980s, never knowing that my grandparents had lived there. Neither my mother nor her siblings ever spoke of the years they spent years at Weld Road and briefly at nearby Hicks Road too.

After discovering my grandfather’s references to living there, I found an online discussion by Kuala Lumpur history buffs about a “Serani Row” at that very stretch of Weld Road and newspaper references too, all saying that many Eurasians had lived there.

But did “Serani” mean only Eurasians, or Christians too? Some say both, with another word, Nasrani, having been used to refer to Christians. And were some of the “Eurasians” at Serani Row in fact the Catholics, like my grandparents?

Some of the people who had come from Travancore, with Portuguese surnames, did not consider themselves Indian. In Travancore, that principality my grandfather came from which later became part of Kerala, “Nasrani” referred to Syrian Christians who traced their history to St Thomas the apostle.

Were these men from Travancore loosely referred to as Nasrani, and was that related to the “Serani” of Serani Row?

In 2022 I went to Seremban, an hour out of Kuala Lumpur, to visit Bertil and Phyllis Lopez for the first time. Phylis’s father was my mother’s first cousin Anthony Paul Pereira, whom everyone called Ando.

Phylis confirmed that her paternal grandmother Francina Rozario and my mother’s mother Isabella were sisters.

When Francina and Paul Pereira had Ando, their first child, in 1917, Francina and Isabella’s brother William Thomas Rozario registered the baby’s birth.

Phylis showed me her father’s birth certificate and there, under the column for race, William Rozario had declared that he, Francina and her husband Paul were all “Eurasian”.

Michael Bastian John, Isabella and their family might well have counted themselves as Eurasian too, fitting in with a community of Eurasians on Serani Row. All their children, however, only called themselves Indian.

In the long list of names my grandfather wrote down in his diary, some from the Weld Road area had names like John Skelchy, F. Demello, F. Soyzas, Paul Fonsecka and C.H. Kraal. After the family moved out of 42 Weld Road, an Alex Dragon moved in. There was a family of Van Dorts nearby too. Some were Eurasian names, some of Ceylonese origin.

In his 1930 diary and House Register, my grandfather almost never mentioned his wife, his sister who lived with the family, or his daughters.

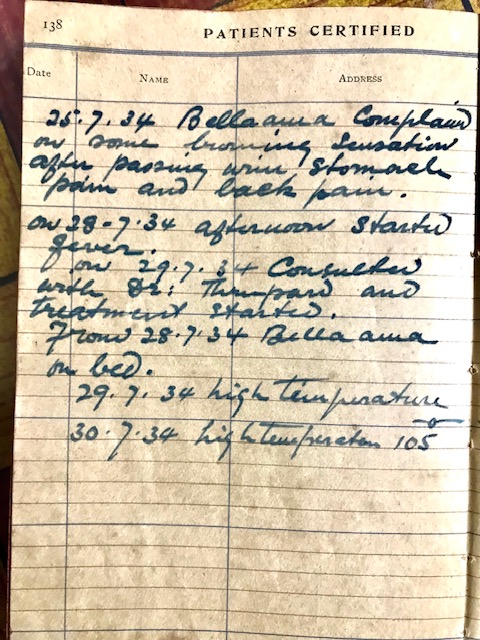

But once, in July 1934, he must have been worried enough about Isabella’s health that he devoted several lines to describing how ill she was for a week.

He referred to her as “Bella-amma” — mother-Bella.

“25.7.34: Bellaamma complained of some burning sensation after passing urine, stomach pain and back pain.

“On 28.7.34 afternoon started fever.”

“On 29.7.34 consulted with Dr [Name illegible] and treatment started.”

“From 28.7.34 Bellaamma on bed.”

“29.7. 34 high temperature.”

“30.7.34 high temperature 105”

Then, no further updates. Isabella recovered, but he did not record that, or hint that he had feared she might die.

Within two months, Michael Bastian John himself was dead.

My cousin Baba, who is in her 80s and living in Taiping, recalls that she was in Kuala Lumpur with her husband and daughters in the 1970s, her mother Girly visited.

Girly, Michael and Isabella’s third child, wanted to see the house in Setapak where the family had lived in the 1920s until she was about 12 years old. She remembered it was near the township’s market.

Baba recalls finding the wooden house on stilts, painted light blue, and that it was one of a pair in the same design, opposite the market.

She remembers her mother’s reaction on revisiting that childhood home.

“She said her father lost everything and was in debt. Mum said it was his best friend who took the house, because her father owed him a lot. Mum looked so sad, I did not ask her anything more.”

My grandfather died two years after he made a light blue Palm Beach suit for his 50th birthday, and nine months to the day he shopped for a necktie before Christmas from Robinsons.

How did he come to that sad end? Sometimes, someone will say he lost all he possessed in a gambling binge. But none of his children seemed to know for sure, or speak of it.

Or maybe they chose never to look that way.