Photo courtesy of Pamela Pereira Mann

One day in 2021, in the midst of the pandemic, a photograph appeared on my phone. It showed a big group of smartly dressed men, women and children, some seated, some standing, posing at what might have been a wedding party.

“This is Pereira Palace,” said Pamela Pereira Mann, from her home in Wollongong, Australia. Her grandmother Francina Rozario and my grandmother Isabella were sisters.

Francina married Paul Pereira, an assistant manager on a Malayan rubber plantation and they had five sons including John, Pamela’s father.

At some point in the first half of the 20th century, Paul and his brothers owned an estate in Malaya themselves, and this picture might have been at the large house on their property.

Pamela identifies her grandfather, standing third from left behind a row of seated women. His wife Francina is first from left.

“Some of our relatives are in the picture too,” she says, but she cannot identify anyone else.

I scour the faces, searching for my grandmother Isabella among the eight seated women, and for my grandfather Michael Bastian John from more than a dozen men.

Is this my grandfather Michael and his bride Isabella?

Are Michael and Isabella the couple seated at the centre, and could this be their wedding day? The face of the woman with flowers in her hair is blurred, but the groom bears a resemblance to my grandfather, from the only photograph we have of him. I can’t tell.

Are they the same man?

A broad-faced woman seated on the right, resembles my other grandmother, Michael’s sister Louisa. She was married with three sons aged three, two and one when Michael married Isabella in 1911.

If that is indeed Louisa, is her husband, my paternal grandfather Davis Colundasamy, among the men? Are their sons – Joseph, my father John and Albert – in the picture too? Where, where, where?

It is utterly frustrating that nobody left a caption, a guide to who’s who, and sad that everyone who might have told us is long gone.

I give up guessing, imagining, pretending I know some of the faces.

But this photograph is precious in other ways.

The clothes the people are wearing, for example. Everyone is in Western outfits.

Several of the men look smart in their three-piece suits with jackets and vests, apparently unbothered by the heat. Some are in light-coloured buttoned tunics.

The women wear the same hairstyle, their hair parted down the middle and pulled back, and there is not a sari in sight. They are in high-necked, long-sleeved outfits, perhaps the chatta mundu, the skirt, blouse and shawl ensemble of Christian Malayalee women. Their necklaces and bangles vary.

There are a dozen children in the photo, the youngest a toddler resting against one of the seated women. A man stands holding a boy behind the maybe-bridegroom at the centre.

A young boy more formally dressed than the other children has found his spot between the seated couple. If this was a wedding, was he the page boy, and was the little girl, all dressed up and posing in the corner by herself, the flower girl?

There is a couple who appear to be European, standing in the second row. This is the only woman who is not seated and, unlike all the others, she has her hair swept up and her dress is different from theirs too.

It is not inconceivable that my grandfather Michael is in the group. He knew so many people named Pereira that if there was a big do at the Pereira Palace, he might well have been there and among friends, if not relatives.

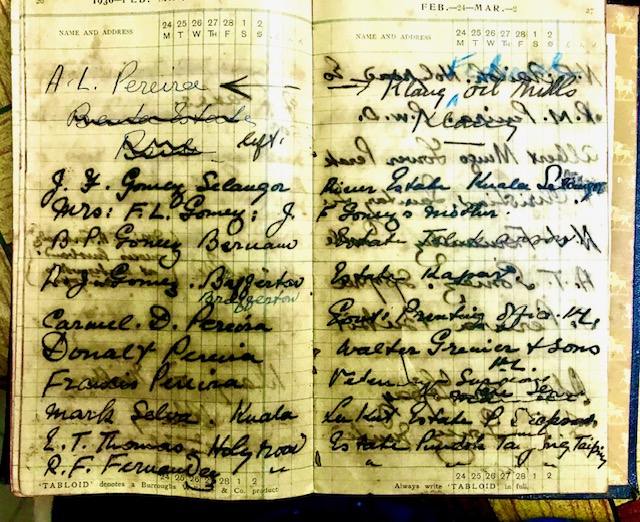

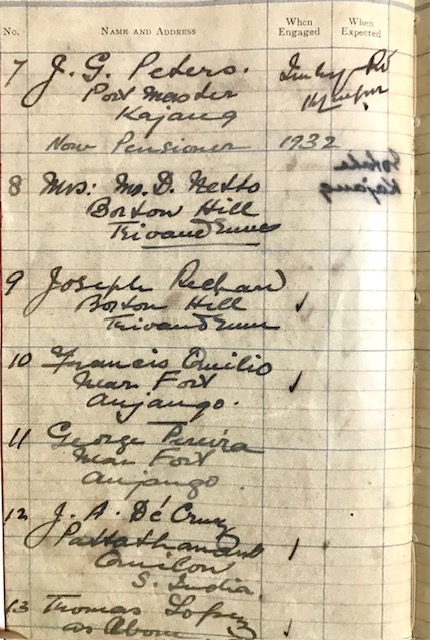

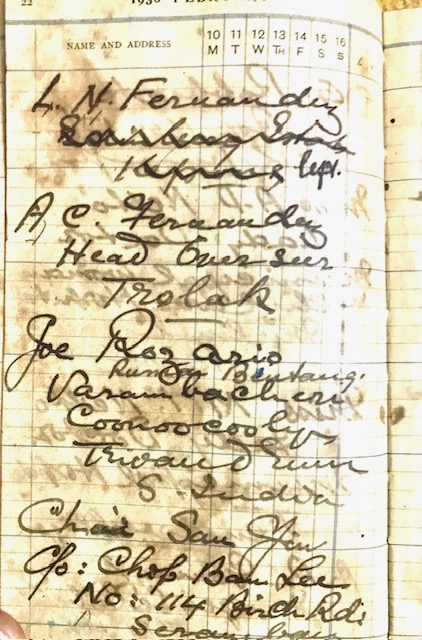

Shortly before he died in 1934, my grandfather wrote down a long list of people he knew in Malaya and India. Their names fill more than 20 pages of the 1930 diary my cousin Bella Panicker showed me in Taiping when I visited in 2022.

In page after page, he scribbled close to a hundred names, as if he was trying to recall or remember everyone he knew who was in India or had come like him to Malaya.

This is not an address list, because there are hardly any proper addresses. Most names come with only a mention of the individuals’ place of work, or the town where they live.

Some are related to him or Isabella, and some dear enough to be their children’s godparents.

There are nine names in Travancore, perhaps indicating where Michael and Isabella’s closest kin came from.

Four are in Trivandrum, including Joe Rozario, Isabella’s brother who returned from Malaya and built himself a bungalow he named Rumah Bintang – “Star House” in the Malay language of Malaya.

Three others are from Anjengo, the fort town by the Travancore coast, and two from nearby Quilon.

There is a “C.B. John” in Quilon. If that B stood for Bastian, this would have been Michael’s brother. And could the C stand for Cyril or Charles, the names he chose for two of his sons?

The largest group in the list are 14 people surnamed Pereira. Apart from one in Anjengo, the rest are in Malaya and mainly in Kuala Lumpur and nearby places like Petaling and Puchong, and a little further away in Klang, Seremban and Port Dickson.

Four Pereiras worked on rubber estates, including John Pereira, at the 10th Mile Cheras Estate in Kajang. He was godfather to Michael’s youngest child, Charles.

The other Pereiras worked at the Railway Goods Shed, Klang Oil Mills, Government Printing Office and a private company, Walter Grenier & Sons.

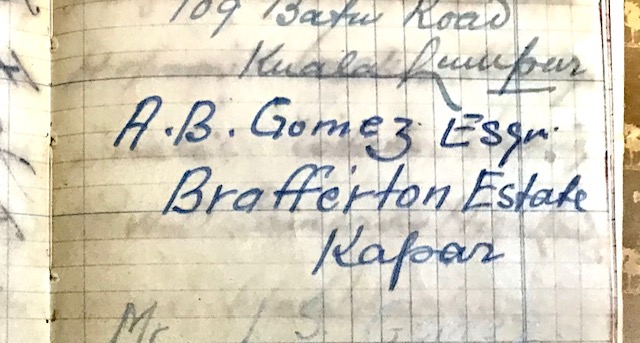

My grandfather’s list also had 10 people surnamed Gomez, six surnamed Fernandez and four, Lopez. Along with those named De Cruz, Coelho, Netto, Rozario, Miranda and Rebello, these pages in the diary describe a group who shared a number of things in common.

Many of the people closest to my grandparents came from the same area, a tight triangle of Trivandrum, Quilon and Anjengo. They are known as Thiruvananthapuram, Kollam and Anchuthengu in the southern part of what is now Kerala.

These men were Catholic, educated in English, Westernised and all decided to leave home for Malaya at the turn of the 20th century. Like the Pereiras, most had jobs on estates, in the civil service, Railways and British companies.

The Portuguese surnames suggest that they were from families who had been converted by missionaries who travelled from Portugal to India from the 1500s.

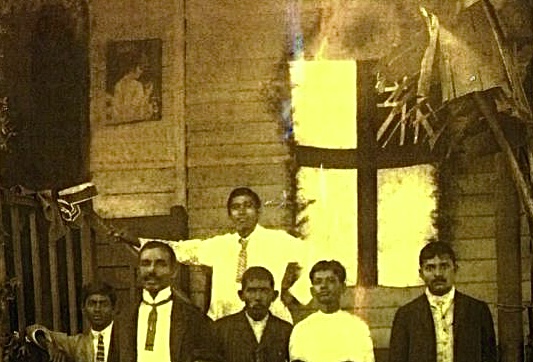

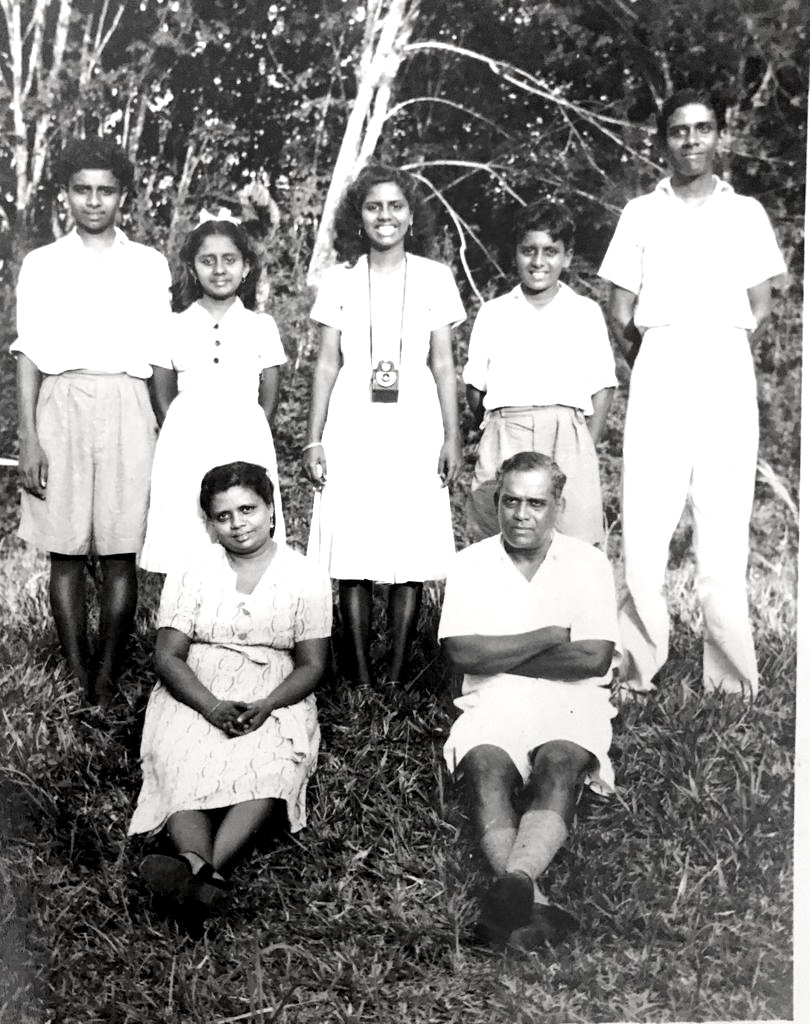

The men, standing left to right: Thomas D’Silva, Paul Pereira, unknown, and Simon George De’Netto. Seated left to right: Lily D’Silva, Francina Rozario Pereira holding her son Hubert, and Simon De’Netto’s wife Camelia D’Silva. Photo courtesy of Phyllis Bernadette Pereira Lopez

The people who became “Latin Catholic” in Travancore were mostly low-caste Hindus who found in Christianity an escape from the cruelty of the caste system, the rigid hierarchical social system that rendered entire communities untouchable, unapproachable and confined to specific jobs for generations.

Conversions took off in Travancore with the arrival of the Jesuit missionary St Francis Xavier, the co-founder of the Society of Jesus. Travelling as a representative of the Portuguese King, he went in the 1540s to India and Ceylon, before moving on to Southeast Asia, Japan and China, where he died in 1552, aged 46.

The Latin Archdiocese of Trivandrum says on its website that by the end of the 16th century there were established Christian communities throughout that southern part of what is now Kerala.

As for who became Catholic, it says as many as 90 per cent of the converts were impoverished fisher folk classified as belonging to “backward communities” and occupying the lowest rungs of the stratified social system.

Discrimination and atrocities against lower-caste Hindus persisted through the 1800s and well into the 20th century, even as there were movements led by Hindus and some Christians to oppose the caste system.

There are accounts of discrimination even among the Christian converts, as deeply ingrained behaviours and attitudes proved so hard to shake off.

At the start of the 20th century, my grandfather and the group of Catholic men he knew broke away from that social system and moved to Malaya.

R.C. Lopez, known as Sunny Achen in the family, with his wife Elizabeth (Aley) and their children at their Sungei Way Estate home. Standing from left: Philip, Mary Magdalene, Theresa, Chrisanthus and Andrew. Photo courtesy of Andrew Lopez.

In this new world, some found jobs in the fast expanding network of rubber estates, where they occupied a mid-level positions, able to speak in English to the colonials who held the top jobs, and Tamil to the plantation workers.

In the civil service of the Federated Malay States and the Malayan Railways, English-educated men like my grandfather and his friends found jobs as clerks, technical assistants and junior officers.

They attended Catholic churches in Malaya, sending their sons and daughters to the Catholic boys’ schools and convents that mushroomed across the peninsula.

There was never any talk of caste in my family through all my growing up years, thank God and my grandfather for that. Nobody talked about how we ended up Catholic with peculiar surnames, when or why.

Our world view, and that of our children, would be Catholic, Indian, Southeast Asian, and we would be free to stay or go anywhere, be anything we wanted to be.

It is almost 90 years since my grandfather wrote down that list of names just before he died.

There is no telling why he decided one day in 1934 to start remembering everyone who moved with him from one world to another, where he would leave his children and grandchildren to make lives completely unlike his own.

His list of names provide mere glimpses of a family story that has remained a mystery for all my life. Mostly, my grandfather still leaves me wondering what to make of these scraps I find.

I show Michael Bastian John’s list of names to a few people I know.

My friend Brendan Pereira in Kuala Lumpur spots both his grandfathers right away and sends me their photos. His father’s father is Isidore Pereira from Hong Kong Estate in Puchong. His mother’s father, listed as “Geo J. De Cruz, Serdang Estate” was known to everyone as “Serdang D’Cruz” for working on the rubber plantation in that district on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur. St Anne’s Chapel, which he built on the estate grounds, still stands, with services attended by Catholic students of the agricultural university there.

“Serdang D’Cruz” left, and Isidore Pereira.

Andrew Lopez, in Kuala Lumpur and in his 90s, identifies “R.C. Lopez” as his father Romuald Constantine Lopez, who ran the Sungei Way Estate where the family had a house with a tennis court. RC was better known in the family as Sunny Achen, and we were all in awe of his children who played the piano and violin and sang beautifully. Andrew, a powerful tenor, performed regularly on Radio Malaya in the 1950s and was known as the Mario Lanza of Malaya. Sunny Achen and his sister Rosalene were my mother Agnes’s godparents.

In Singapore, my friend Mary Magdalene Pereira spots her father’s first cousin, “S.J. Pereira” in Port Dickson, and tells me the initials stand for Stanley John. And “J.F. Gomez” in Kuala Selangor is her mother’s first cousin, Joseph Francis Gomez.

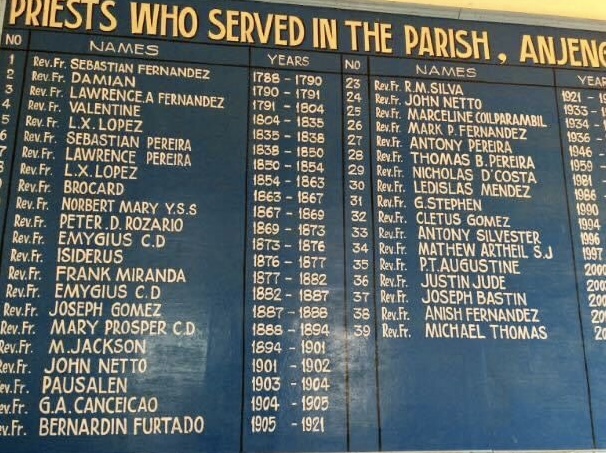

She also sends me a photo from a visit she made to Anjengo, where so many of her people came from. It shows a plaque at St Peter’s Forane Church, listing the parish priests going all the way back to 1788.

There they are again: Pereira. Fernandez. Rozario. Gomez. Lopez. Miranda. Netto. And the rest of them.

My grandfather’s Travancore tribe.

Next: Weld Road and “Serani Row” in Kuala Lumpur. My grandfather makes himself a suit for his 50th birthday.

I don’t know where this will go, but I’ll just write down what I know and maybe someday someone will figure it out.