The Covid-19 pandemic was an abnormal season of staying home, severely restricted movements, wearing masks, a nagging anxiety about illness and, as it dragged on, a creeping sadness that we might not see people we cared about in other places again.

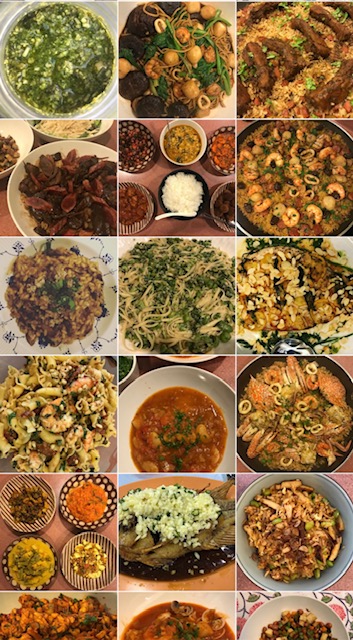

I cooked a lot at home in Singapore during the pandemic. For several weeks I looked out for a yellow bird, a black-naped oriole that came to the window and whistled. I subscribed to MasterClass online and watched famous authors talk about writing, and famous chefs sharing their kitchen skills and recipes.

I kept in touch with people by WhatsApp, exchanging messages, pictures and videoclips.

In Kuala Lumpur, my mother’s dementia was advancing at a frighteningly rapid pace. Sometimes on videocalls, she had no idea who I was.

I began sending her videos of me, singing hits from the 1940s and 1950s, songs I heard at home growing up. Afterwards, my sister Audrey and niece Imelda would send videoclips of Mum watching me on the phone and singing along.

During that enforced, unnatural down time I also spent hours poring over my grandfather’s Family Register, trying to prise any insights from his entries that were little more than a list of births and, twice, deaths.

As soon as we could travel again in 2022, the first place I went to was Kuala Lumpur, to see my mother who had just turned 93.

It was like a window would open, allowing her to remember happily that I was her son, and then it would slam shut, I would be a friendly stranger again and she would be content for me to be beside her or hold her hand.

We did not know that day in April 2022, when I went out to lunch with my mother, sister Audrey, her daughters Imelda and Carmen and my cousin Patrick John, that Mum would be gone before Christmas.

I had printed out the pages of my grandfather’s notebook to show everyone I saw on that trip. Look at his beautiful handwriting, I’d say. Look at the names of all his children’s godparents. Look, how sad that baby Bertha died at nine months. Some would say, poor Grandma Isabella, she had so many babies!

After Kuala Lumpur, I went north to Taiping, a small, soothing town dominated by a hill and a beautiful lake garden, where most of my cousins are from. My mother’s sisters Girly and Elsa, who settled in Taiping, had 29 children between them. Only a few still live there.

My first stop in Taiping is always to see my cousin Baba, in her 80s and living on her own in a two-storey house in the Pokok Assam area where her parents had their home too. Her two daughters are in Kuala Lumpur and Italy.

The eldest of Girly and Gregory D’Silva’s 16 children, Baba always had a special connection with my sisters and me because sometime in the 1960s she lived for a while with us in Kuala Lumpur. She got married from our house, the prettiest bride I’d ever seen.

Sitting together in her living room, surrounded by family photographs and holy pictures, we talk about everything. The tennis on TV. Cataracts, aches and pains and doctors’ appointments. Family. Long Ago Stories. Whatever is bothering either of us. Prayer and miracles and wonders. She informs me I’m not allowed to die before her.

I show her our grandfather Michael’s House Register, but she cannot help me to fill in the blanks. Like so many of my oldest cousins she has only fragments of our family story. But she is encouraging, tells me to keep looking and will be happy to learn more herself.

In Kamunting, another part of Taiping, some of my Panicker cousins occupy three single-storey terrace houses in a row.

My aunt Elsa had 13 children with her husband Peter Panicker but in Kuala Lumpur, we saw less of the Panickers than the D’Silvas and did not even know all our cousins’ names.

Yet, when on a whim I visited Bella, Philomena and Francis in 2019, they were so warm and welcoming, I hoped to see them again. The three unmarried siblings shared one house, with two of their married sisters in houses on either side.

In 2022 I was in their home again for a cooking demonstration and lunch. In WhatsApp messages with Philomena during the pandemic years, we’d talk about makan time, and the food we ate at home. When I said I was curious to know if her family made our family recipes the same way I did, she said: “Come, I’ll cook for you.”

Bella, the eldest Panicker daughter named after our grandmother, always had a reputation for being a formidable cook, taking after their mother Elsa and preparing countless meals for their large family.

Now I found that Bella had been elevated to kitchen consultant, seated in a chair supervising, as Philomena went about making our lunch of chicken curry, beef cutlets, cucumber pachadi and kappa, boiled and cubed tapioca tossed in a lightly spiced seasoning.

All the preparation had been done, the vegetables chopped and onions sliced, whole spices spooned out and ready for the processor, and the meat-and-potato patties we called cutlets only had to be fried.

Philomena cooked one thing after the other expertly, pausing near the end to let Bella taste and approve before turning off the heat. “Put a little more salt,” Bella would say. Or, “Add some vinegar.”

The meal was delicious, the chicken curry tasted so familiar the recipe had to be from our grandmother Isabella, from more than a century earlier. My mother cooked it almost exactly this way too, calling it “Mama’s Chicken Curry”.

The kappa was new to me. My cousins told me that during their family’s hard times, a big bowl of boiled tapioca cooked this way was the entire meal waiting for them when they returned from school. To make it tastier with a little crunch, my aunt Elsa added snipped and fried dried anchovies.

After lunch, I took out my folder with the printouts of our grandfather Michael’s House Register to show my cousins, pointing out names, dates, places and events.

When I reached the end, Bella said: “We have something like this too.”

She went into her bedroom and emerged a short while later with a bundle, it was something wrapped in a cloth bag.

Placing it on the dining table before me, Bella said her mother Elsa had cherished this single reminder of her father Michael Bastian John all her life and it was preserved like a treasure.

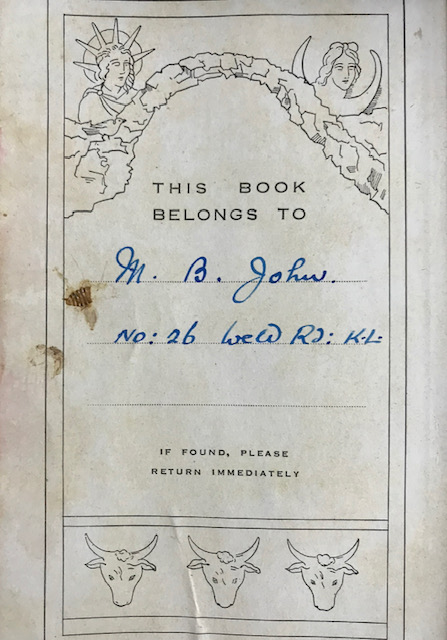

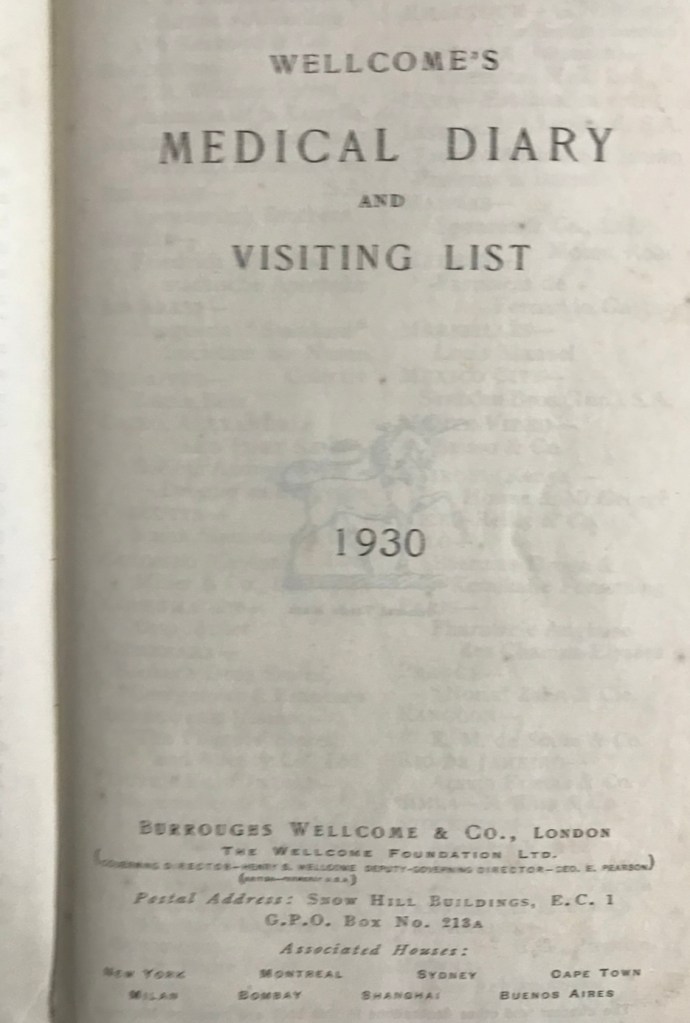

I could barely contain my excitement as we opened the bundle to reveal a “Wellcome’s Medical Diary and Visiting List” diary for 1930. The inside cover page said This Book Belongs To… and my grandfather added in his handwriting: M.B. John, No. 26 Weld Road, KL.

In black ink, his handwriting covered more than three dozen of its fragile pages. It was nearly 90 years old.

There were shopping notes, lists of names, a record of people who had passed on, a few lines of anxiety during an episode when Isabella fell ill, and what struck me as a mood of sadness and regret.

Although it was a 1930 diary, Michael Bastian John’s last notes were written in 1934, mere months before he died.

Next: My grandfather’s Travancore tribe of Malayalee Catholics.

I don’t know where this will go, but I’ll just write down what I know and maybe someday someone else will figure it out.