One day in 1917 my grandfather Michael Bastian John took out a small notebook and named it ‘MB John’s House Register’. He kept it for 17 years, opening it only to record the most basic information about significant family events. The nine pages he filled tell of marriages, births, baptisms and deaths, each page numbered and signed.

The entries stop one day in 1934 with a note that his fourth son, Theodoret, my Uncle Teddy, had started school on May 15. Four months later, on September 20 1934, M.B. John died, nine days short of turning 52. He left a wife, my grandmother Isabella, and 10 children aged four to 19, five girls and five boys. My mother Agnes was his youngest daughter, and she was five when he died.

These few pages of a palm-sized notebook, and a photograph, are all I have of my maternal grandparents who travelled to Malaya at the turn of the 20th Century from Trivandrum in Travancore, part of present-day Kerala, the coastal state in southwestern India that calls itself God’s Own Country.

The notebook is in Amsterdam with my cousin Tony John, the son of my Uncle Charlie, M.B. John’s youngest child. I never knew of its existence until the day Tony photographed all the pages of the notebook and sent them to me over the phone.

It was a precious gift late in my life. I have spent hours scrutinising the sparse contents, drawing bits and pieces of a family history I knew too little about because so many of the main players who might have filled in the blanks died young over the first half of the 20th Century.

The more I pored over these pages, the more questions I had, that will never be answered. Yet, each time my grandfather took out his notebook to add a new item, he left those who came after him hints of who we are.

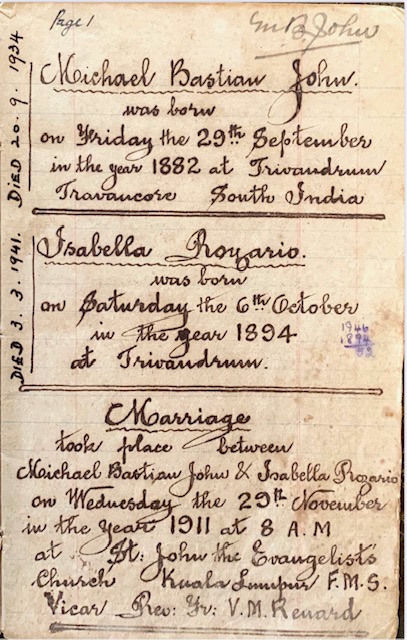

Page 1: Michael & Isabella

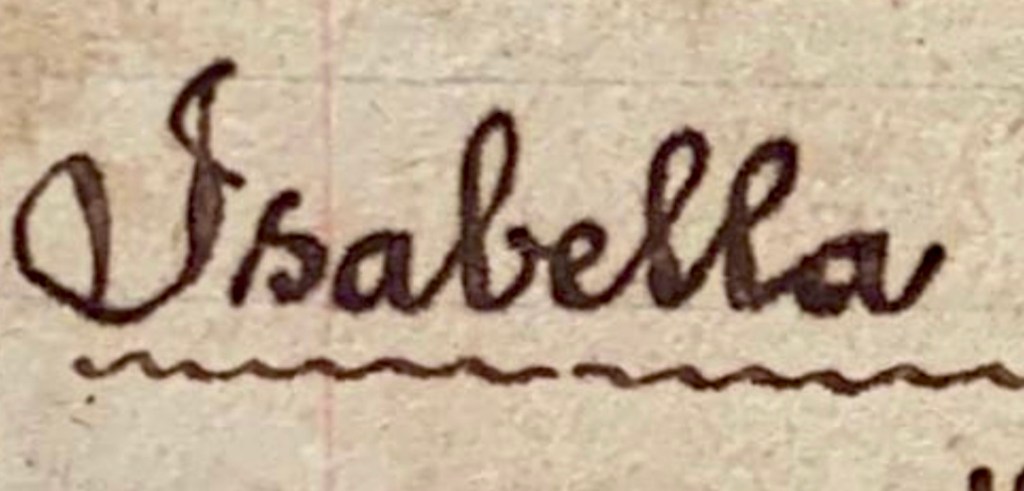

Before I even begin to read the contents, what strikes me immediately is my grandfather’s calligraphic handwriting. It appears best on the first page. It is as if when he decided to start and picked up his ink pen, he concentrated on writing as perfectly as he could. I know the special pleasure of writing the first lines into a blank book, and I sense my grandfather felt it that day.

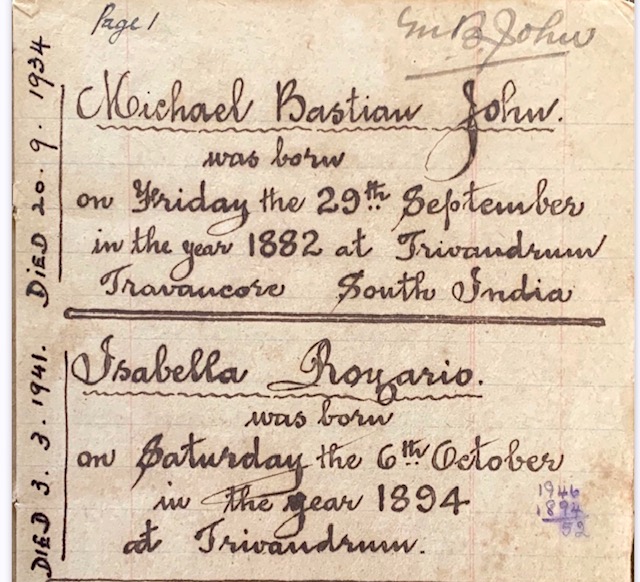

Michael Bastian John was born on Friday the 29th September in the year 1882 at Trivandrum, Travancore, South India.

Isabella Rozario was born on Saturday the 6th October in the year 1894 at Trivandrum.

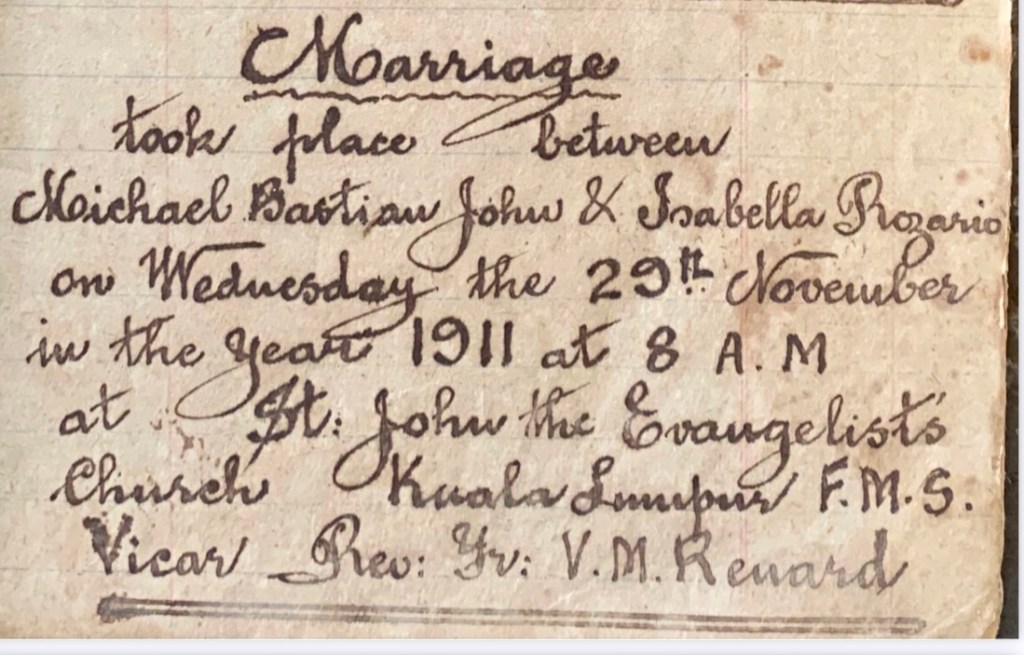

Marriage took place between Michael Bastian John & Isabella Rozario on Wednesday the 29th November in the year 1911 at 8am at St John the Evangelist’s Church, Kuala Lumpur, FMS. Vicar Rev. Fr. V.M. Renard

The top left side of the page is numbered Page 1. And at top right, he signed MB John. On the left, next to the details about Michael and Isabella, someone else has recorded their dates of death.

For Michael, Died 20.9.1934; and for Isabella, Died 3.3.1941.

My grandparents were from Trivandrum, now Thiruvananthapuram, when it was part of the princely state of Travancore. They were both Catholic.

Michael Bastian was a draughtsman with the survey department and in his 20s when arrived in Malaya sometime during the first decade of the new century. He was educated in English, and perhaps the draughtsman’s precision explains his neat handwriting, as well as his habit of signing off on every page. He had at least two sisters in Malaya. One of them, Louisa, was married to Davis Colundasamy, my paternal grandfather, and they already had three sons by the time Michael married at the age of 29.

The “FMS” in my grandfather’s entry about his marriage says he came to Malaya as part of a massive wave of immigration from South India that began in the late 19th century. British colonialists had brought together the peninsular Malayan states of Selangor, Perak, Negri Sembilan and Pahang as the Federated Malay States (FMS), expanding on their earlier establishment of the Straits Settlements made up of Penang, Malacca and Singapore.

By the turn of the century, there was a severe shortage of workers for the rubber plantations and tin mines that made for a flourishing economy and a boom in construction of roads, railway lines and landmark buildings in the FMS capital, Kuala Lumpur. The British were also in India, and began bringing in labourers from South India for plantation and construction work. Chinese immigrants steered clear of these jobs, working instead on tin mines and doing business in urban areas.

A second group of English-educated South Indians and Ceylon Tamils arrived to take up mid-level jobs in the civil service and railways, and on plantations. It was a period when South India, which had no jobs for the young men finishing school, provided the push, and Malaya, with its booming economy, proved the pull for young men like Michael Bastian John.

Isabella Rozario came to Malaya to get married. I cannot imagine what it was like to be a girl of 16 and living at home in Trivandrum, and be told she was going to get on a boat and travel to Malaya in Southeast Asia, to marry a man 12 years older. The wedding took place barely eight weeks after she turned 17. Was that birthday the last she spent at home in India, to which she never returned, or her first in the new country where she would remain for the rest of her life as a wife, mother of a large brood, and a widow, before dying at 46?

Michael and Isabella were married at eight in the morning on a Wednesday. The Church of St John the Evangelist was the original Catholic church on Bukit Nanas, a historic Catholic area in the heart of Kuala Lumpur. When the Cathedral of St John the Evangelist was built nearby, the old church building was decommissioned and became Fatima Kindergarten, which I attended before starting primary school next door at St John’s Institution. I spent 13 years at St John’s, never knowing that my grandparents were married on Bukit Nanas, in my kindergarten.

Their presiding priest, Father V.M. Renard, was from the Paris Foreign Missions (MEP), which sent missionaries to Malaya and Singapore. There was a French priest at St John’s Cathedral all the years I went there.

On Page 1 of MB John’s House Register, I gather these fragments from the briefest of details about my grandparents, who were both long gone by the time I was born in 1953. What I love most are the stylish flourishes of my grandfather’s penmanship, his elegant capital letters and the graceful cursive flow of his perfect lowercase letters.

He does not describe anything. He does not say if his bride looked pretty that Wednesday morning, or tell what she wore, or what he felt as this girl became his wife. But his rendering of her name is to me a piece of art. Of everything on this page, I am drawn most to his Isabella.

Part 2: Isabella Rozario, my grandfather’s bride

To be continued. I don’t know where this will go, but I’ll just write down what I know and maybe some day someone else will figure it out.